A Last Visit to the Rubin

You have until October to visit, see the art and ponder eternity with the not-so-hungry ghosts who sold ties and measured suits.

The Rubin is a museum in Manhattan that specializes in Himalayan and Tibetan art filled with audacious images that make even more audacious demands. It’s been a regular stopping point every year or so since it opened in 2004.

It’s closing in October. If you’re in town, I’d recommend it.

I stopped by the other day with my wife. We banged a few gongs, spun a series of tin soup cans arranged like prayer cylinders, and watched a digital animation about a person coming apart at the seams, unwinding the illusion of life and rejoining the cosmos.

The bowl with three seams

In addition to paintings and sculptures, it also has a bowl made out of a lacquered human skull. Under the skull is a little placard explaining why it’s more or less okay to have it on display. I forget the reasons, but it’s pretty cool.

The skull-bowl is a pretty common image in the paintings. There’s always someone holding one, brimming with bloody pink brains. Usually, it’s a blue demon, fat, fearsome and all too happy with the situation. Usually, he’s also trampling the body of some poor fool.

There are some demons who are snacking while making time with a well-bangled, fanged woman. These are the hell realms. And if they fascinate you, then you might want to look into that. It can catch up with you in a bad way, or so I’m told.

Arrow in your eye

Of course, it’s not all demons and skull bowls. There’s a rainbow bridge and well-meaning bodhisattvas who’d like to help you out. They’re very calm but hard to please.

Up high, in the yellow and blue, they gesture with empty hands. Around them, clouds drift and flowers blossom as glowering death’s heads.

They’ll spend lifetimes daring you to do something like drive an arrow into your own eyeball. They don’t make the ascent easy but make it possible.

The wheel

Demons and bodhisattvas are both prominent on the wheel, called a bhavacakra. They man the cycle of getting wise and getting unwise, of approaching liberation from all sorrow, and descending to seemingly eternal starvation and rage.

The wheels at the Rubin are jammed with details. Clockwise is just one way to visually follow it. You can slightly unfocus your eyes and try to hold the whole thing in your mind at once.

Image courtesy of the Free Software Foundation

These wheels have always made a powerful impact on me, like this is the most we will be allowed to see. It’s a hallucination, but more than just that, it’s a style guide for future hallucinations that seems to be offered with generosity, warm wishes and no small amount of pity.

You can also look at it from the edges to the center. The outermost ring of these images is a guy going through the paces of life, getting born, walking around, visiting cities, riding in boats, making love and getting old.

From this perspective, daily life is the suburbs of an ongoing crisis, or the shadows of an object obscuring the light from the center. When you do take a step toward the center, you run into heavens and hells, incredible pleasures and torments. Take another step, in and you find three animals, a chicken, a snake and a pig - chasing each other. You’re not even dealing with anything human, but forces, represented by animals simply because there aren’t any better ways to represent them.

A monster with a crown of skulls is holding the wheel. Claws, fangs and a sneer. But look at the hands and feet. Is that a costume? If so, who’s wearing it?

A corrupt dog track

It’s a busy image. But we’re busy on the inside. Imagine, just for fun, a corrupt dog track, like we had in New England when I was a kid.

Imagine playing all the parts: You’re the greyhound chasing the mechanical rabbit, and the mechanical rabbit, and the real dead rabbit thrown to the dogs afterward. You’re the devoted dog trainer, and the guy from the kennels who overfed the dog so it would lose, and the guy who bet his kids’ lunch money on that greyhound. And you wonder why you feel so crummy all the time.

Calling all men to Barney’s

The museum is in an old department store with a chrome spiral stairway through the middle, with a frosted skylight above it, filtering sunlight through the space from the center.

The space itself puts me at ease, and I can imagine another life where I might buy a small stack of overpriced dress shirts there.

I’ve never been a huge shopper, but I remember the store. A buddy of mine got a job out of Parsons doing windows for it. He made some trips upstate to go antiquing with the other window dressers, then they let him go.

Arts and crafts

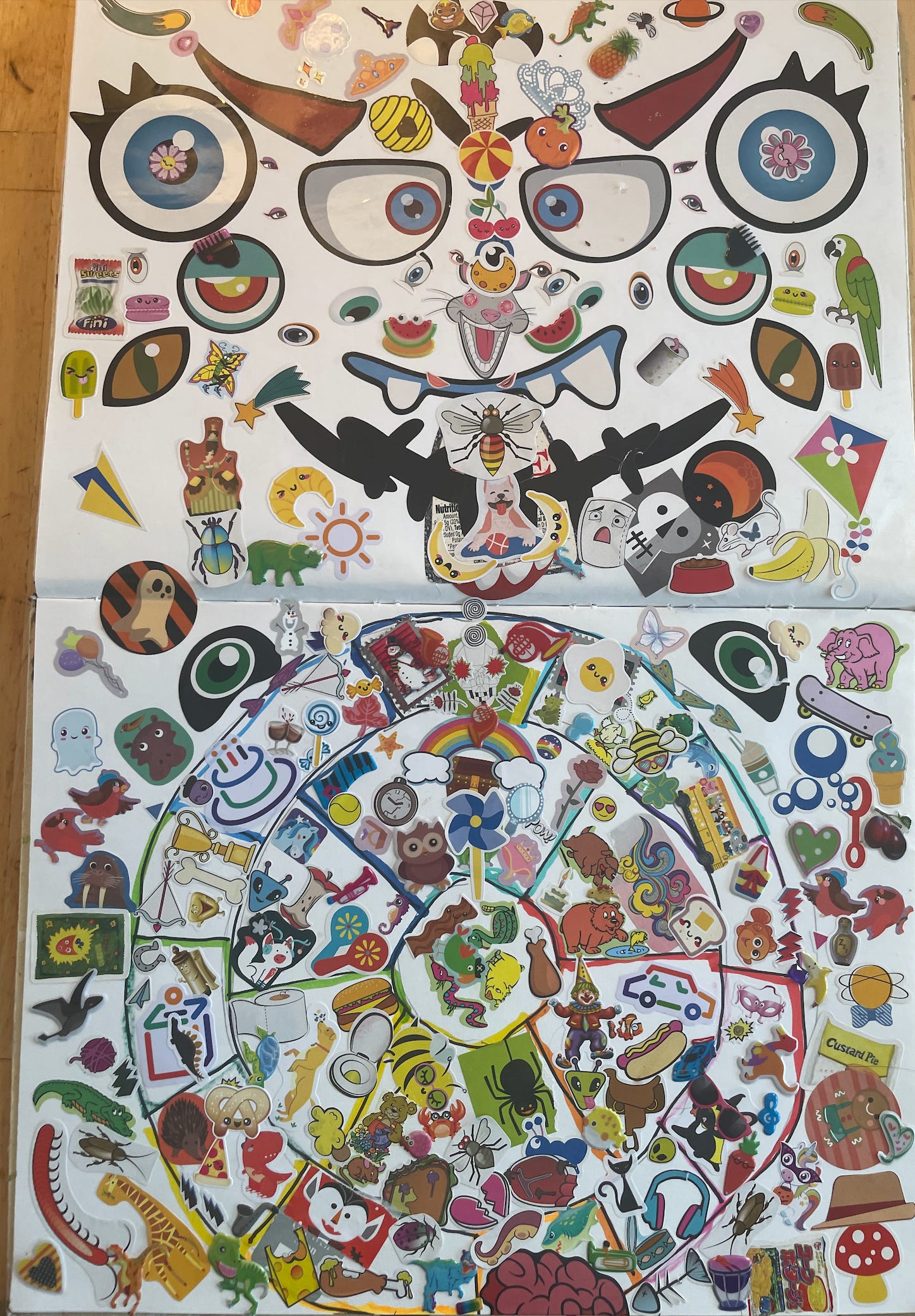

After my most recent visit, I was thinking about the wheel. I wanted to make my own, but I’m a laughably bad draughtsman. Then I remembered my daughter’s 8-year accumulation of sticker sheets of sticker books. I begged, borrowed and stole some time, and went to work.

Kiddie-Sticker Bhavacakra, Colin Dodds, Copyright 2024

As anyone who’s done much hallucinating knows, the images appear because the mind is desperate to find a language for the unknown thing \it’s experiencing. It grabs what’s at hand - a Smurf or Homer Simpson or Barbie or a vapid celebrity.

One reason that the Tibetan imagery is deliberately so bizarre is to give a student a clearly hallucinatory language to understand what’s happening to them when they die. When you die, one massive problem is that you just don’t want to accept that you’re dead, so you hallucinate a shopping mall and a parking lot over the whole thing. This is the premise of E.J. Gold’s The American Book of the Dead.

Memorable visits

Once I toured the museum in a wheelchair. It’s a nice way to look at art. Just bring crutches to a museum, and they’ll give you a loaner wheelchair. At the time, I had a ripped achilles tendon. But it’s not like they checked. After smashing my injured foot into the wall of an elevator, my wife got the hang of it, and we had a good time.

I took my daughter there after Covid, and we spent some time at an exhibit unpacking all the elements of the wheel of life, and a display that really does explain how the lost-wax process creates sculptures. Then we got to bang the gongs.

One afternoon, playing hooky from work, I visited. But I was stalked by a tour group of retirees the whole time. They wouldn’t stop asking irritating questions - the guy with the teeth, is he the one you have to make happy to get to heaven? Some days you can’t buy a break.

It made me a little crazy - the promise and demands laid out by the art, and the tour group’s blithe refusal to hear it. I went to the cafe downstairs and at least got a poem out of it. In it, I misspelled the name of the museum and took a few potshots at the tour group.

But eventually, I get to the real source of my frustration, which is the incredible personal, emotional and intellectual demands that the art seems to make. Here’s the highlight:

There are hierarchies among the saintly and the saints

But only for those who require bosses

There are settlements in the unblemished imagination

But only for those who require shelter

Swinging down

When I was working on my sticker wheel of life, I was thinking about the motion downward into illusion and the climb back up again. It’s not the kindest mirror. Getting older brings more doubts, which require a willing suspension of disbelief in order to function. It occurred to me that this isn’t a good direction of travel.

In one of the wheels, archers on the border of one of the false heavens fire arrows down the slope of the wheel at the refugees newly risen from hell. It caught my eye. Another unkind mirror.

Every day is a preparation - a little for death, a little for more life.

When a good thing goes away

New York is a busy place for busy people. It makes demands on demanding people. It’s a dynamo of images, sensations and illusions. It’s dirty and expensive and some of us can’t keep away from it. The Rubin has been a powerful counterpoise.

It’s sad to see it go. The loss is, of course, minuscule compared with what’s happened to actual Tibetan culture and the actual Tibet in my lifetime. It’s enough to make you resort to poetry, this by Walt Whitman:

"the unseen is proved by the seen, Till that becomes unseen and receives proof in its turn."

Now this place that exalted seeing, travels to the unseen. There, hopefully, we who remain seeing and seen can offer proof of what the museum, its artists and their world tried to show.

You have until October to visit, see the art, sit a while in the cafe, to walk the staircase and ponder eternity with the seemingly not-so-hungry ghosts who sold ties and measured suits.

Selected bibliography

The Rubin’s website

The Rubin’s explanation of the Wheel of Life

Walk Whitman’s Song of Myself

E.J. Gold’s American Book of the Dead

Antoine Volodine’s Bardo or Not Bardo

The film Jacob’s Ladder

What's all this about a corrupt dog track???