Gathering in the Sparks

Harry Smith, Kabbalah, Tony Soprano, the eradication of regret, and a late-arriving glimpse of the great work of mid-life.

Getting older is hard to understand. Each year I become more of a stranger to one more person you’ve been.

Like many of my peers, I’ll catch myself being angry or anxious about something, and ask “who even am I?” Former impulses cease to make sense. Capacities dim. The fun is over. If I was going to do something, I would’ve done it already. If something was going to happen to me, it would’ve already happened.

But something is happening. I’m starting to figure it out, though I can be a little thick. I often can’t understand what I’m doing until I’ve been doing it for a while.

Landing the plane

Lately it can seem like life consists of either getting into or getting out of trouble. You sin then repent. You rip then run. You incur then shed karma. You are born, press deeper into social, professional and familial existence, then retire, withdraw and die.

The essential “getting into or out of trouble” division struck me recently, because of all the energy I spend these days staying out of trouble. My days pass in a strange land, where I have little to gain and much to lose by speaking my mind, or from delving much deeper than necessary into any given interaction. What I want from a given workday is mostly just for it not to stick to me.

When I talk with friends in our forties, one term for our shared concerns is “landing the plane.” We’re up at 40,000 feet. We’re in enough trouble.

Money & death

One reason we’re in trouble is that we don’t have enough money. But who does? A guy with five dollars in his pocket on a brisk walk toward a speeding bus has plenty. A billionaire with bad luck, bad habits and a healthy heart does not.

Money is a karmic paradox. Money promises to get you out of trouble. But getting money gets you into more trouble. It saddles you with responsibility, makes you complicit. Money is why you can’t afford to die or achieve enlightenment.

Death is a different kind of paradox. Death is why life is so short that everything you do and experience must matter. Death is why everything you do and experience may not matter at all. Hurry up and act on that information, you’re dying.

“It has something to do with money and death,” is how David Chase described his inspiration for The Sopranos. He never said what exactly.

But a thread connects those two important things that otherwise ignore one another assiduously across a crowded room. The connection is necessarily illicit, and the tension is clear.

Spitting & distance

In fiction, you get into all kinds of trouble. You can have characters do and say things that horrify you, simply because there’s something solid and redolent about that particular horror. In poetry, you can do similarly, and just say that the wind said it, or something.

You “put it out there.” You extricate it from your own private miasma to investigate it further, or just to make it someone else’s problem.

But where does it go, once it’s out there? It can be forgotten, though forgetting is less straightforward than if you’d never said or written it down. That was the point of speaking or writing in the first place, like choosing to live. It’s the choice to get into more trouble.

Peak experiences in the valley

As a young man, I got into some trouble, but could have gotten into far worse. I did things I wouldn’t do again, things I wouldn’t recommend, and things I wouldn’t air in public. I took a lot of risks with my health, sanity and freedom. I had a lot of fun, and a fair share of the other things.

There wasn’t always a lesson in these experiences. So where do they go? What purposes do those memories serve? What purpose does any memory serve? What is this ever-swelling bag of experiences I carry around for?

Harry Smith & decoration

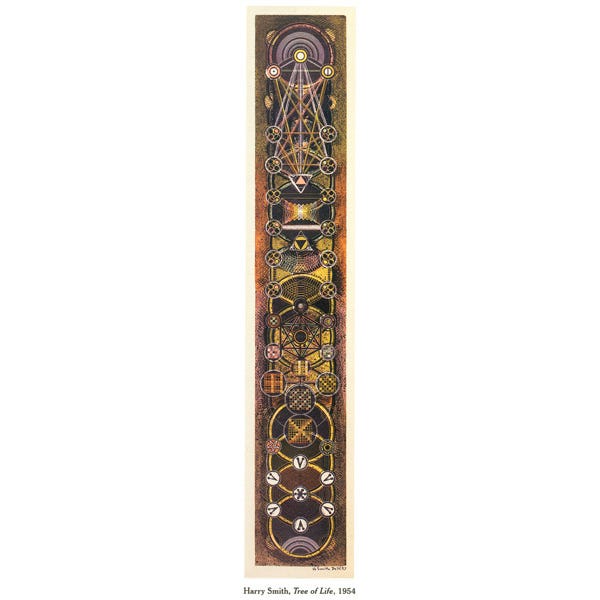

We had a house fire and moved to a new apartment last August, and I needed some new art for the walls. One thing I happened upon was a print of Harry Smith’s Tree of Life in the Four Worlds, a modified Kabbalistic tree.

I’d studied the subject in college, and had an enthusiasm for an American reimagining. I had my own ideas about the Kabbalistic tree of life, and a sense of what I failed to understand. The picture on my wall reminded me of a moment in my life when I had more excitement and time for mystical contemplation.

“Colin, he used to sit in saloons wondering about the meaning of life. Now all he does is work all the time,” my accountant mused the last time I saw him. As someone who works all the time, my accountant seemed pleased with the development.

The guy at the frame shop admired Smith’s Tree. Its beauty is magnified by my own nostalgia and unresolved yearning.

The tree of life

The traditional Kabbalistic tree is a vertical diagram of the universe, showing the steps that the omnipotent, omniscient fullness of G-d takes on its way to our own bewildering reality. It’s an attempt at comprehension and sympathy for this world of ours.

Credit: Wikipedia

That complicated journey from the heavens to the earth is not the end of the story, though. The tree can also be read as a map back up the ladder. The downward flow of divine creation into matter and the upward striving of us material creatures combine to make the Tree look a bit like an electrical circuit, with energy constantly flowing up and down through the common qualities, conflicts and conundrums marked by each node, or sephiroth.

Harry’s Tree isn’t so different, though taller, with more nodes than the conventional tree, connected in more ways. There’s a system here, a more obscure one.

A hidden interpretation

The print of Harry Smith’s Tree arrived at our home with a double-sided sheet of paper featuring short essays about the piece. It was a busy time of unpacking boxes in the heat.

After cleaning out a junk drawer, I found the sheet of paper again in February. And one essay, by Khem Caigan, struck me upside the head. He had a different perspective on the Tree. He posited it was “a set of empty screens or frames providing places for the sorting & storing of ideas & images… to extend the powers of the soul as well as those of memory.”

He saw the Tree as a mnemonic device, like a memory palace, that could hold the entire universe. Using the Tree, you could take the experiences and insights from your own life, and assign them to different elements. In so doing, you could reconfigure your own life from a time-bound assembly of “then this happened and then this happened” into a form with which you might confidently encounter the divine.

Caigan’s essay did more than shift how I looked at the Tree. It contradicted the weariness of mid-life, and the way that my own life had begun to feel. Memory can often feel like dross, a crust accrued on the aged. Here it was at last, presented as a source of strength that only needed to be better marshaled.

A note on magical objects

I’m not a superstitious person. Things work or they don’t, often based on mood, luck and timing as much as anything.

The Kabbalistic Tree is something that seems to hold the capacity for absorbing and rewarding contemplation. The contemplation and its reward belong to the person doing the contemplation.

The object is inert. But some objects seem to pay off better than others. Your results may differ.

Non, je ne regrette rien

Caigan’s interpretation of Harry Smith’s Tree may seem arcane. But simply put, it says that the choice in life may not be as simple as deciding whether to get into or out of trouble.

You don’t need to repent - you’re probably, secretly at least a little proud of your worst sins anyway. You can gather back the trouble. The trouble connects you with a broader world, and allows for a fuller approximation of the entire universe.

What this view doesn’t allow for is regret, in the sense of disowning anything you’ve done. This is different from remorse, which is a gravity that one memory exerts upon another.

Dry bones

There’s a section in the strange and incredible Book of Ezekiel where the prophet finds himself in a valley of discarded human bones.

G-d asks Ezekiel if these bones could live again, and Ezekiel says he doesn’t know. G-d tells Ezekiel to prophesy to the bones. And the bones talk back. They don’t much like being bones. They’re cut off from each other. They have no hope. Ezekiel prophesies some more and the bones reconnect and come back to life.

Each bone was once alive. It was part of a creature who received some care and succor from the world. Cast off, they’re scary - the stuff of Halloween, a warning that you’re in a dangerous place. But there’s a way to rejoin and reanimate them, and it begins in speech.

Rounding the corner

Until recently, essays have been hard for me. I’ve tried nearly every other genre first - poetry, plays, novels, screenplays and aphorisms. They’ve allowed me to speak from other voices, under other names, to argue indefensible points and to take wild shots in the dark.

An essay, on the other hand, comes from a point of view that coincides as completely as possible with my byline.

It’s the way of life to learn things out of order. I can be a little thick, and often can’t understand what I’m doing until I’ve been doing it for a while. The poetry, fiction, aphorisms and screenwriting have been a way of marking the world with what’s most vital, private and mysterious to me. These essays have been a way of gathering them back together according to some geometry that’s unclear this close up, but which feels necessary.

Mid-life

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Homework to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.