The Length of a Breath

On ambition and attention, music videos and prestige cinema, poetic controversies and the pleasures of peek-a-boo.

I used

to break up

sentences like

this.

But I’m retired from poetry, so I don’t do that anymore. But I still feel the push-pull that makes poetry so consistently difficult and occasionally rewarding. Poetry’s an ambitious form. It wants to do big things in a small space. It wants eternity. It wants to transcend time. The clock, however, is ticking. The reader is getting restless.

The reader started out restless or else they wouldn’t have opened up a book of poems. They want something important, and they want it now.

How do you do so much in so little space? William Blake assumed that readers had the same attention span he did for secret, epic verse histories of the universe. They mostly didn’t. We remember his epigrams, his quips and his short lyrics.

Ambition and attention

This tension between high ambitions and limited attention shows in the question of how long a poetic line should be.

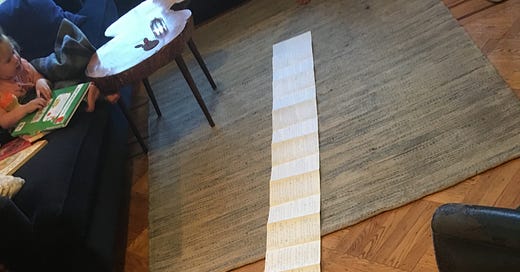

Walt Whitman liked long lines, the length of a breath, and Allen Ginsberg followed suit. The long lines addressed the tension by creating a sense of rhetorical acceleration, building up a head of steam in a genial, conversational way, and then using that momentum to propel a prophetic and grandiose tone. Emily Dickinson liked smaller lines, where each word balances like a boulder in a cairn. Her shorter lines depended on the idiosyncratic qualities of words, and the compounding idiosyncrasies as they met each other and shone light into the reader’s own experiences.

Both approaches work, but with effects so different that it seems crazy to drop them all under the single heading of poetry.

Mtv

People argue about attention spans. They’ve been saying attention spans are getting shorter since I was a kid.

Music videos were a big deal back then, which were supposedly degrading the attention span of my generation. They ran 3-7 minutes apiece, which was, in hindsight, too long. Only occasionally would you get something like Thriller that could hold your attention the whole way through. If you go back watch a few videos, you’ll notice a lot of repetition and filler just to get to the three-minute mark.

Grownups felt about music videos the way people of my generation feel about TikTok videos.

But the short form makes sense for the content. Most young people don’t have much to say, but they don’t want to be left out. Shorter forms let them get in, look good, do their thing, and get out before anyone realizes, oh, that’s all there is to it.

Oscar bait

The prestige drama film, on the other hand, keeps getting longer.

The technique is, if you can’t be good, to be long. This shows up in other forms, especially books. The effect is to stick the viewer with a strong sense of sunk costs, so they can’t badmouth the film without admitting they’ve badly squandered their time. The hope is to win an award, and turn the movie into homework in the years ahead.

This bad-faith artistry is doing more to suffocate cinema

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Homework to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.