Messages for People Who've Forgotten Your Language

What connects Yucca Mountain in Nevada and the Trois Freres cave in Southern France? An urgent desire to communicate with distant generations. And what's worth saying to the people of 12,024 AD?

The Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository is the primary storage facility for all the radioactive materials enriched in North America over the past eighty years. Uranium, plutonium and the byproducts stored there will remain deadly to humans in ten thousand years and beyond.

But how can we warn those people? What will survive ten thousand years? Some form of this civilization? Our language? Our symbols? Given the difficulties that I have explaining television “channels” to my eight-year-old daughter, that’s a tough question.

For Yucca Mountain, there was a contest: Design a warning sign to keep people away from this deadly vault. People came up with all kinds of visual devices to express the danger to their great-to-the-hundredth-power grandchildren. Giant X’s, blackened stone blocks, fields of giant thorns and even genetically modified trees. It was nice to see smart people thinking beyond the next fiscal quarter for a change.

The question was a huge one. In ten thousand years, where will you be? What will people be like? What will they care about? And lastly, what do you owe them? These aren’t things people talk about much, given the headlines and the deadlines.

Sure, there was that disingenuous moment, a minute ago, when some of pious tech people touted Longtermism. There’s also the now-demolished Georgia Guidestones and the titanium capsules filled with the steel-engraved writings of L. Ron Hubbard inside a New Mexico mountain. And they all beg the reasonable question: What do we owe our very-distant offspring?

What persists

The real challenge with something like Yucca Mountain is getting inside the minds of people who haven’t been born yet. If you have something highly urgent and highly specific to say to those people, how do you say it?

The problem is fundamental. We’re learning animals. Our instincts only go so far. If everything goes great, a baby still takes a year to walk, a year to talk. And we rely on language for most of what allows us to survive. When we learn a language as babies, we have the shared experience of our home and family with which to pair the words. We pick up written language from the verbal, and a second language from the first, or from a new shared frame of experience.

A common tongue turns to jargon, to decoration

Sounds great. But when we have to make a leap from a foreign frame of experience into a written language, it can take centuries, if its even possible. The written language Linear A, which preceded the written Greek language, remains indecipherable to this day.

Or, take the Rosetta Stone. For centuries, people had tablets, carvings and scrolls of the written Egyptian language all around them that they simply couldn’t read. Only when the language was put up side by side with a known language, on a carved royal decree, did it fall into place.

You need a point of reference to translate. The almost hopeless difficulty of retrieving a lost language is apparent from the decades and immense efforts, leaps of logic, intuition and computing that went into finally reading Mayan inscriptions.

The Yucca Mountain contest, while cool, was disappointing. So many of these guys wanted to recreate the ‘50s radioactivity symbol (but, like, in stone) that it was embarrassing. They simply couldn’t imagine a vocabulary common to the world those far-future generations would inhabit, so they didn’t try. Or else they were playing to the judges.

The best ideas in the Yucca Mountain contest had a visceral impact. And they revealed the limitations of communicating across vast spans of time. They implied that the only shared environment they could expect to reference is one where fire burned things black and sharp things caused pain.

Enter Arthur Corwin

Ice Age humans believed they could point to a frame of experience that they would share with their distant progeny. And from that shared experience, they could construct a language.

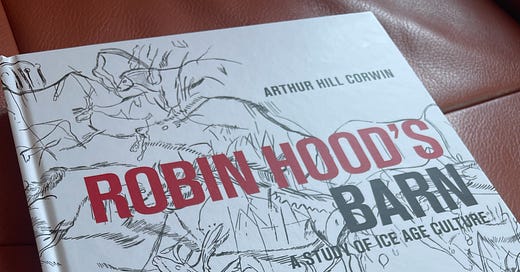

Like the Yucca Mountain warnings, the language would necessarily be visual. Like the Yucca-Mountain designers, our distant ancestors had urgent information about threats to our survival - threats that would continue to be immediate even thousands of years later. This is a major element of Arthur Hill Corwin’s book Robin Hood’s Barn.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to No Homework to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.