Trips

The odd career of a literary work from beyond, and my own decades-long journey alongside it.

Works discussed

- The Tibetan Book of the Dead - translated by W. Y. Evans-Wentz - 1927

- The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead - Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert - 1964

- The American Book of the Dead - E.J. Gold - 1975

- Jacob’s Ladder - Bruce Joel Rubin - 1990

- The Sopranos, season six - David Chase - 2006

- Enter the Void - Gaspar Noe - 2009

- Bardo Or Not Bardo? - Antoine Volodine - 2016

- Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths - Alejandro G. Iñárritu - 2022

- Trip - Amie Barrodale - 2025

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, also known as the Bardo Thodol, is an ancient text about what happens when the bubble of an individual personality pops at the instant of death, what follows, and what can often go wrong.

It’s a book about a process that happens to someone or other all the time, and eventually to each of us. It takes place in a realm immediately adjacent to all of human life, specifically the weeks after one’s death. The subject matter is about as timeless as you can get. But the book exists in time. It was written down in the eighth century in Tibet, then lost, then discovered in the 14th century. There’s a story the Buddha tucked the whole volume away in the mind of one of his original followers, who finally coughed it up after a few dozen incarnations.

The book was introduced to European and American readers in 1927, with the first translation by W. Y. Evans-Wentz. Those first readers were high on electricity and combustion engines, but down on their own kind, following the first of hopefully only two world wars. Since then, the book has been hugely influential in many different contexts.

Bardo

At the center of The Tibetan Book of the Dead is the idea of the Bardo. There are a few Bardos - daily waking life being one of them. But the term as it’s commonly used in English, and the way I’ll use it here is the Bardo immediately after death.

In it, one is confronted by alternately gorgeous and horrifying visions - reflections of one’s own self and one’s own life. In some ways, it’s like life. But the succession of actions and consequences turns very slowly in life, while in death it is more sudden, less predictable and less forgiving. This is double jeopardy, the lightning round, where the stakes are higher, where losers win and winners lose.

Solo trip

The Bardo is a distinctly lonesome afterlife. It’s just you, facing your own grubby bargains, grandiose delusions, failures of empathy and personal generosity, rage, lust, greed and so on in different guises. Seeing through the disguises is supremely important. It goes on until you cry uncle and go hide in your next incarnation, or the clock runs out around day 49, and you go on to your next incarnation.

The book’s emphasis on seeing through the projections of your own mind spoke to the psychiatrists and psychologists who’d hoped to turn the soul into a science during the early 20th century. Carl Jung famously wrote about the book in the 1930s.

Hallucinogens and Harvard

Less than forty years after its introduction to the scholarly and esoteric intelligentsia of the West, the Tibetan Book of the Dead popped into popular culture. Timothy Leary repurposed it as a guide to LSD trips in the form of The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead (1964). Always half a huckster, it’s hard not to see the Harvard-credentialed Leary borrowing spiritual bona fides for a highly mercurial and suggestible experience - one that’s as easily religious as it can be deeply atheist. The book is an over-serious rehash, which the Beatles made into a sitar-saturated track on Revolver.

Fire in a cell

Timothy Leary-and-company’s book was the first version of the text to make its way into my hands, at the age of seventeen, thanks to the savvy clerks at Newbury Comics in Framingham, Massachusetts.

I had it with me one night in 1994 or ‘95 when some friends and I went to a police station in a nearby town to try and get my late friend Joe Martin out of jail. He’d acted out to some cops breaking up a house party and was in for disorderly conduct. Held until morning, we couldn’t get him out. But I thought a jail cell would be horribly dull without a book, so I offered my copy of it the book to Joe. The jailer said that Joe could have the book, or he could have his cigarettes and lighter. Not both. So Joe handed me back the book through the bars.

Perspective

Now that I’m older, I’m more dubious about the conflation of the LSD trip and the afterlife, but mostly because I’m more comfortable with the conflation of everyday life and the afterlife.

Being older, I get that most teenagers aren’t into The Tibetan Book of the Dead. At the time, I didn’t care. I was wild and full of energy and not easily satisfied. I wanted to rip the lid off of the world. It seemed like the biggest favor I could do for everyone, or at least the favor I was most inclined to grant. And being older, I rarely wonder if I was crazy then. If not for the close calls and the lost pals, I’d worry more often that I wasn’t crazy enough.

“What is truth?”

is the question asked by Pontius Pilate, perhaps ironically, perhaps in contempt, perhaps to lure a reticent suspect out into the open.

We’re all pretty certain that all of us will die. But no one knows what happens when we die. People, however, believe certain things. To believe is to participate. But also vice versa. Spending your life with an idea will endear it to you. Reading will convince you, eventually. Writing will convince you twice as fast. I think what happened to L. Ron Hubbard was that he started out trying to write a religion for profit, and wound up a believer, all because of writing.

So, who should you believe? What should you believe? I am partial to what biblical scholars call the criterion of embarrassment. If something contradicts or stands at a tangent to the purpose of the text, it may well be true. The Good Book is chock full of strange statements, occurrences, characters and outbursts. It can feel like the exact opposite of the book a sane administrator would design to start an organized religion. An editorial policy of we don’t understand it, so leave it in, may be the sole reason we know of many miracles.

Unease and embarrassment

E.J. Gold’s American Book of the Dead (1975) was another close contact with the Bardo Thodol. The book was making the rounds in the East Village by Tompkins Square Park, among old hippies and Gurdjieff enthusiasts. This was around 1997-’98. I was in college - I must have been about twenty years old.

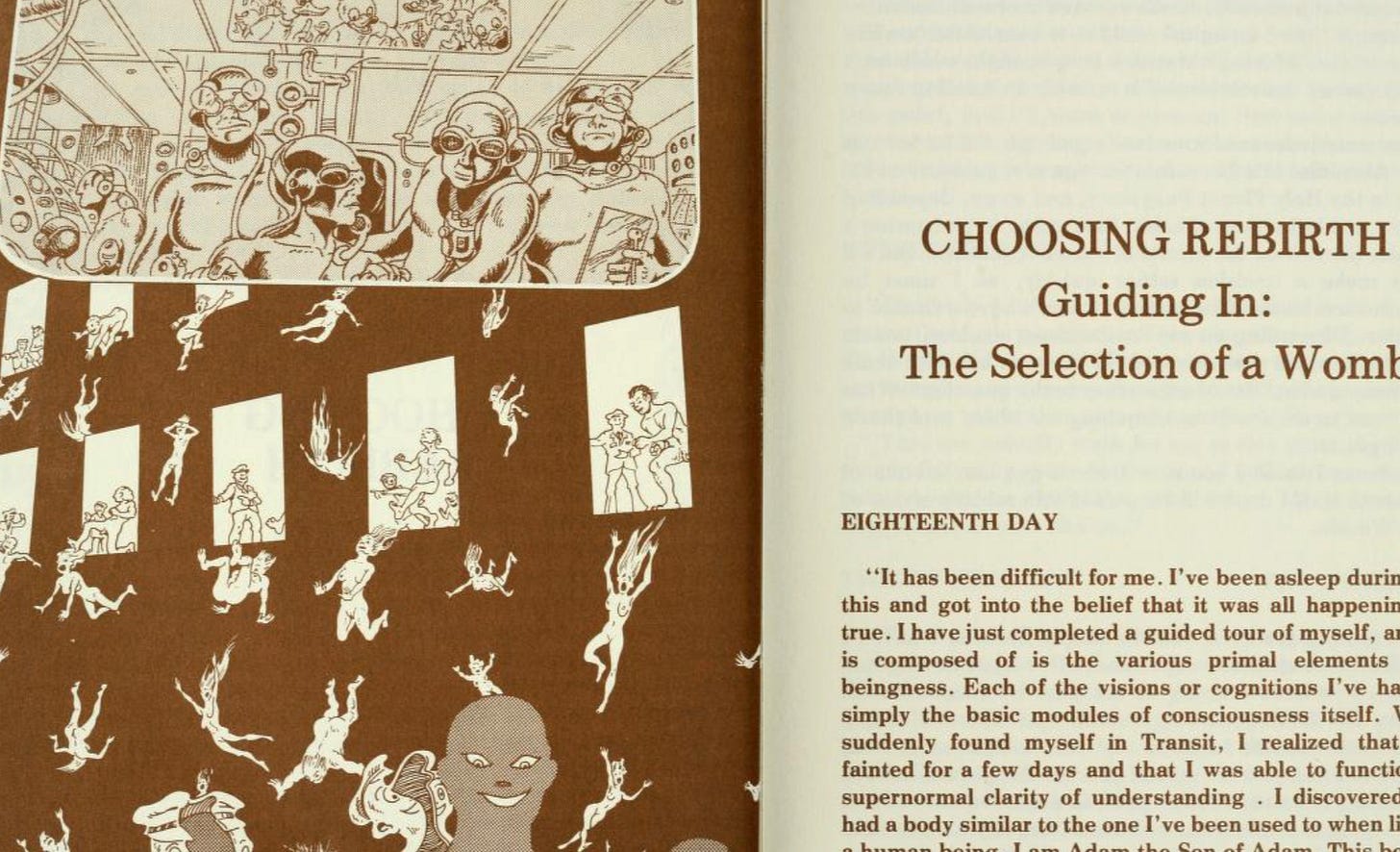

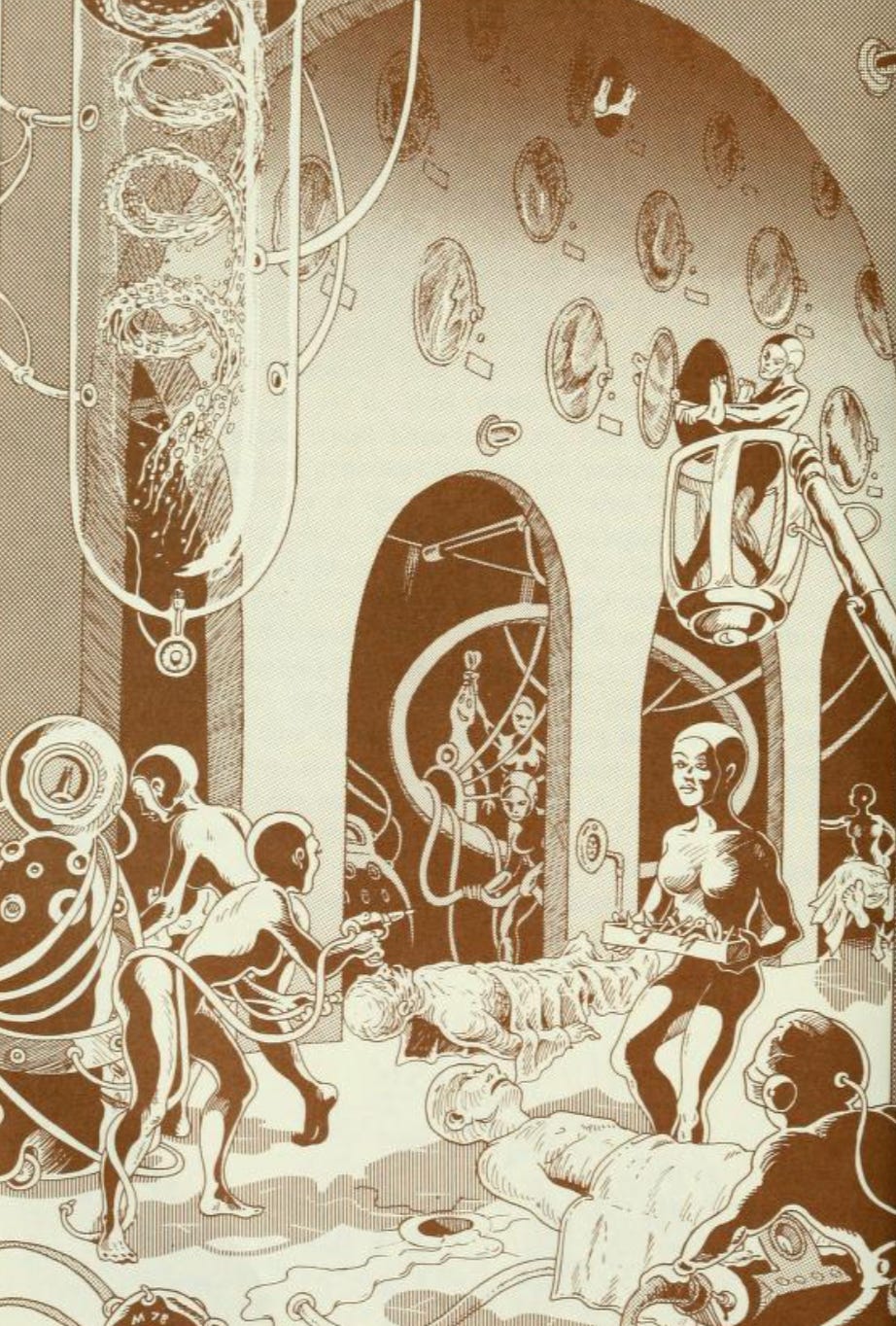

My late friend Harry Essex introduced me to the book one evening in his apartment on North 11th St. in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I remember the details because I read half the book in a sitting that night. Then I walked out past the fenced-in lot of broken bricks with the green copper dome of the Eastern Orthodox church beyond it, into McCarren Park feeling almost skinned, raw and naked under the sky. Some of this is due to the illustrations:

(Illustrations by George Metzger, Copyright 1978)

In terms of content, The American Book of the Dead The book is another beat-for-beat take on the Bardo Thodol, but with the aim of counteracting the illusions most likely faced by an American in the 1970s. It’s eerie. In the introduction to the edition I read, Gold starts out by saying “this is a book I really didn’t want to write.”

No marketing

In the Bardo, there are paths to so-called god-realms into which one can be born. These are entire universes where one’s every whim is catered to. But they’re not forever. And going to one is generally considered a costly misstep.

The thing about the Bardo is that it’s not heaven. No one meets you at the curb to take your bags and show you to your room. It’s a chilly day without a coat. You’re subject to exhaustion, horniness, resentment, rage and anxiety. And it only gets worse depending on how you respond. It’s test, test, test and risk, risk, risk, all the way to the Clear Light of the Void, which sounds like the biggest risk of all.

It’s not something you put in the brochure for new members. It possesses that criteria of embarrassment.

Street smarts (where the streets are not real)

The afterlife in the Bardo is deceptive. You get accused, chased, judged, seduced and falsely reassured. It’s all being done to you, but the ones doing it to you are projections. The power of any of these interrogators or lovers or teachers depends entirely on your response to them. They’re as big or as scary or as sexy or as truly wise as your response would have them be.

In that way, it’s like dealing with a bully or a prostitute. They each provoke and then wait on your response for their next move. Nothing is to be trusted entirely. Reality is predicated on your responses. The experiment is invalidated, and you’re well and truly in the soup. Like in life.

Are you dead? Yes, you.

The biggest problem with the afterlife, according to commentary within and adjacent to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, is that you may not ever realize that you’re dead. This is the reason for meditation practices you envision deities that are outrageously gorgeous or horrifying and often fucking, or in the phrase of the curators, embracing. By garishly outfitting the figures of one’s fantasies with a necklace of human heads while licking gore from a brain pan, one has a better chance of recognizing that they even are a fantasy.

Otherwise, you’re just hanging out with your good-looking roommate while they start to make out with their boyfriend/girlfriend. It’s kind of hot at first, then you get uncomfortable or annoyed, and decide to go to bed. Your bedroom is comfortable, but the door is small. It’s a bit of a struggle. But three’s a crowd, and so you squeeze out of the living room to alleviate the discomfort. And presto-whammo, you’re a diaper-shitting baby, with all of that ahead of you, again.

Bardo Or Not Bardo?

Antoine Volidine’s Bardo Or Not Bardo (2016) takes place in a near future that’s politically chaotic, corrupt, totalitarian and precarious in terms that are alternately intimate and global. I bought it from a seeming book truck less than a hundred yards from where I lived at the time in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn.

The book is beautiful and disgusting. It flickers from the living to the dead and from the latrines of a prison to the selfless recitations of the temple. The book gives special emphasis to the true purpose of the Bardo Thodol, which translates to something like Liberation Through Hearing in the Intermediate State. The purpose of the text is that you’re supposed to read it, loudly and continually in the presence of the dead, so that they don’t end up incarnated and back on the slab again, or at least so they don’t end up roadkill next time around.

It’s an exacting, exhausting and selfless thing to do - reading aloud for 49 days to a corpse. In the book, the setting is one of civil wars, torture and betrayal. In the book, the people who read to the dead are a reminder that dignity, and by extension humanity, is nonexistent except where one asserts it.

Tricks

In Bardo Or Not Bardo? treachery is the rule for the living and the dead. The secret police watch our characters, who never know which side of the interrogator’s table they may find themselves upon. The dead embark in a hostile landscape where the womb of rebirth lurks everywhere. It’s a bed. It’s a trench in a battlefield. It’s an escalator that gets smaller towards the top.

The womb may look like something else, but you know what it is. It’s a trick, but not really. You may lie to yourself, but you know what you’re doing. It’s interesting how many things in life happen like that: accidentally-on-purpose. You go to rebirth mostly because you’re tired. But are you tired? Or just something you equate with being tired? It’s a time of too much consciousness. The worst part of losing your body may be losing your eyelids.

The Bardo on film

As an influence, The Tibetan Book of the Dead isn’t a book that filmmakers have tried to capture, but one they’ve tried to catch up with. Enter the Void (2016) by Gaspar Noe is probably the most literal interpretation, and the most dogged pursuit of the book.

This is a strange and difficult film. A man is killed in Japan as part of a drug deal, and we travel with him, seeing through his eyes as he travels through his afterlife. In this murky state, he moves like a peeping tom, following the sexual antics of those around him through love hotels, attracted to and repulsed by the bright flashes of orgasm that offer distraction, and ultimately, human incarnation.

For a movie based on a spiritual text, it’s graphic, even pornographic, and very deliberately so. The deities in Tibetan art are often lascivious. Sex is, in the realm of death, a popular habit in which to hide. By extension of the logic of the Bardo, it’s also a place to hide in life.

There’s also BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, (2022) by Alejandro G. Iñárritu. The film, though, isn’t so much about the Bardo, as it uses the Bardo as a narrative non-structure and as an arena for interrogations as part of what’s essentially a character study.

Of films that illustrate the deceptive, erotic and frightening aspects of the Bardo, the best is, unquestionably, Jacob’s Ladder (1990, and don’t bother with the remake). The film itself never references The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and reserves its sole intellectual name-check for Meister Eckhart. The screenwriter of Jacob’s Ladder, Bruce Joel Rubin, had gone to Nepal in the 1960s, and even met the Dalai Lama, who offered to be his personal instructor. Rubin opted instead for a guy from Brooklyn. In his Hollywood career, Rubin made his fortune with the more-accessible Ghost (also 1990).

I saw Jacob’s Ladder in the theater at the age of 13, and though I didn’t understand it, it did something to me. I certainly didn’t like most of the things I did understand at that age, much less what they all seemed to add up to. Even if I had no clue what, Jacob’s Ladder felt like it put me on the scent of something.

The movie speaks to some of what it must be like to die, if you didn’t want to admit it, and if you did have some high-power psychic resources to pretend you were still alive. Eventually though, things start to creep in. Photos get lost. Loved ones become half-strangers seen through a pane of glass. Death unfolds in the perfect disguise of life. Eventually, someone - a parent, sibling or child - waits there to take your hand.

Kevin Finnerty

David Chase is a serious man. And given all the wind in the world at his back, he unfurled the sails in 2006 to take the large and variegated audience of The Sopranos into the afterlife of his most famous creation, Tony Soprano.

Always leery of his hippie bona fides, Chase throws us off the scent by opening the season with William Burroughs’ interpretation of the Egyptian afterlife. But what follows after the shot by Uncle Junior is pure E.J. Gold. Tony comes to consciousness in a hotel restaurant - a place so bland it may as well be AI. After all, what is AI, but the averaged-out memory of what we’ve seen. Who is Tony now? He doesn’t know, but who really does know who they are?

He has a new name, though, a name connected with the concept of infinity.

That first night, he has a chance to disappear into the universe, to follow a strange lady. As they’re about to consummate their union, there’s a bright light. This is the first high bounce, when a person has the best chance at dissolving entirely. But something’s wrong. There’s an attachment. The woman says she could tell he was thinking of his children. The moment’s gone.

Then he’s lost his identification, and a group of Tibetan monks make accusations against the person they think he is. He needs help that he can’t ask for. He goes to a gathering, seeking answers under an assumed name. Something calls to him from inside, but it doesn’t feel right. It’s a nightmare precisely because Tony believes it’s really happening. To put this into a crime show! David Chase! As a character on the show might say, the balls on this guy!

A recent novel

The latest entrant into Bardo literature that I’ve encountered is Trip, a novel by Aimee Barrodale, released last fall.

It’s a great book, funny and poignant. So many of the books on the Bardo - on the personal-development, religion and new-age shelves - tend omit humor and honest sadness from what’s supposed to be a universal experience. They carry over the stress, fear and reverence, but ignore the honest sadness of leaving a life that held much to love. They go heavy on the horror and the temptations, but leave out the sadness and the laughs.

Barrodale’s book is a first-person account of the narrator after her death. She dies at a conference in Nepal about death and the afterlife, which gives cover for the characters’ insightful but brisk conversations on the nature of consciousness and mortality. Dead, she discovers that her autistic son is in trouble, and possesses a colleague to try to rescue him. The author tries to do a lot of things in the book, most notably bringing humanity, empathy and humor to a realm too often depicted without any of them. And she succeeds.

What are you going to do about it?

The way you and I think of death or don’t think of death is highly individual. It’s unique to each person, and often deeply private.

It can also be extremely touchy. People have used stories about the afterlife to intimidate and manipulate one another throughout history. For many, it’s so sore of a subject that it’s easier just to write it off altogether. And people who have a satisfactory tradition or personal theory usually don’t want it fiddled with.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead and its cultural afterlife have fascinated me for a long time. But I never proselytized much. If someone asked what I thought, I’d answer. And I’m always happy to lend a book to a friend or acquaintance, which is probably why I couldn’t locate my copies of The American Book of the Dead and Bardo Or Not Bardo? while writing this. But I never read the whole thing out after the death of a loved one, mostly I suppose because they never asked me to. Based on what I’ve read about the Bardo, it seems like a bad time to be introducing new material.

Fiction?

The works in this essay span a lot of genres: religion and spirituality; personal-development; fiction; new-age; film; counterculture; death and dying, and a few others. It begs the question - what exactly are we talking about here? We’re talking about a very old and very vivid idea concerning something that happens to all people.

And, on our ways!

Thirty years ago, I was a young man. I was interested in visionary poetry, in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and what America had to offer. I was young and tireless then. But there’s only so confusion, consternation and consciousness that any of us can take.

Though being chastened by the years, I maintain that the outcome is far from decided. Most of the demons we face are real, but also not really. They’re only as fearsome as our fear, as evil as our revulsion. Most of the time, to ask a demon what’s going on with them, and have them answer, is to make something other than a demon of them.

I set this up as a book and movie review. Movies and books are ways of winding string around some glimpse of what life and death really are. Movies and books may have been nothing by the time the riddle really lands in our laps. But they may remind us. They may offer comprehensible words and images when what’s happening to us becomes incomprehensible.

Selected bibliography

An essay on a recent death

An essay on guides through the afterlife

An essay on a now-disbanded collection of Tibetan art

An essay on Jacob’s Ladder and other horror movies

William Burroughs’ Seven Souls

Antoine Volodine’s Bardo Or Not Bardo?

Aimee Barrodale’s Trip

E.J. Gold’s The American Book of the Dead

The way you weave personal memory with literary analysys is stunning. Your take on Jacob's Ladder as the best Bardo film rings true, especially compared to more literal interpretations. The detail about EJ Gold saying he didnt want to write the book perfectly captures that criterion of embarassment. Really aprecciate how you bring humor and honest sadness into discussions of death.